Scientists fold RNA origami from a single strand

RNA origami is a new method for organizing molecules on the nanoscale. Using just a single strand of RNA, many complicated shapes can be fabricated by this technique. Unlike existing methods for folding DNA molecules, RNA origamis are produced by enzymes and they simultaneously fold into pre-designed shapes. These features may allow designer RNA structures to be grown within living cells and used to organize cellular enzymes into biochemical factories. The method, which was developed by researchers from Aarhus University (Denmark) and California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, USA), is reported in the latest issue of <em>Science</em> .

Origami, the Japanese art of paper folding, derives its elegance and beauty from the manipulation of a single piece of paper to make a complex shape. The RNA origami method described in the new study likewise involves the folding of a single strand of RNA, but instead of the experimenters doing the folding, the molecules fold up on their own.

"What is unique about the method is that the folding recipe is encoded into the molecule itself, through its sequence," explains Cody Geary, a postdoctoral scholar in the field of RNA structure and design at Aarhus University.

"The sequence of the RNAs defines both the final shape and also the series of movements that rearrange the structures as they fold."

"The challenge of designing RNAs that fold up on their own is particularly difficult, since the molecules can easily get tangled during the folding process. So to design them, you really have to imagine the way that the molecules must twist and bend to obtain their final shape," Geary says.

Nano size honeycombs

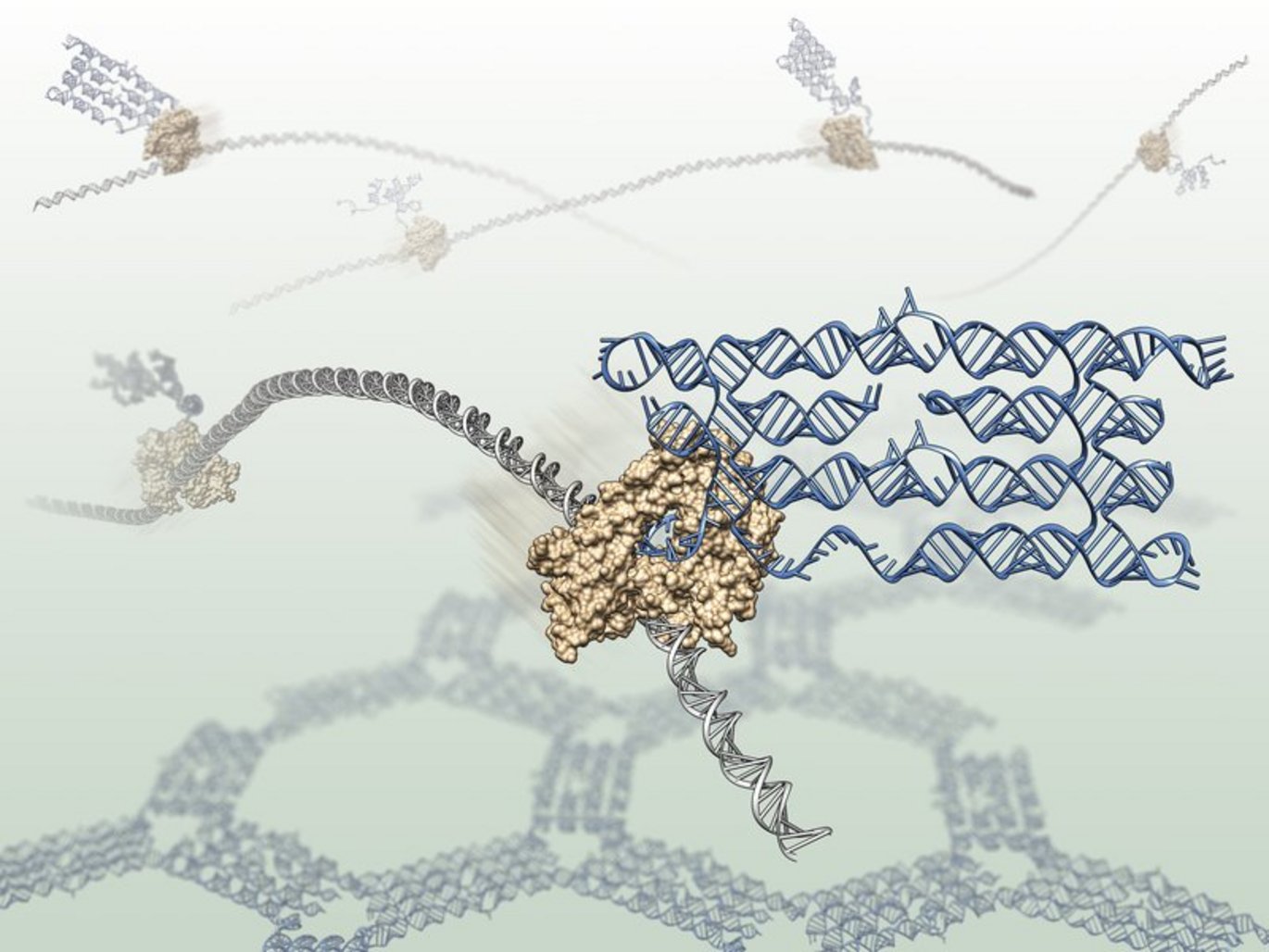

The researchers used 3D models and computer software to design each RNA origami, which was then encoded as a synthetic DNA gene. Once the DNA gene was produced, simply adding the enzyme RNA-polymerase resulted in the automatic formation of RNA origami.

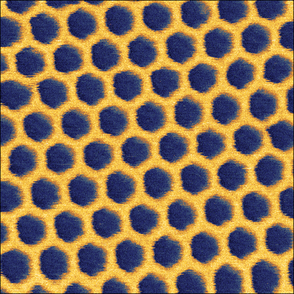

To observe the RNA molecules the researchers used an atomic force microscope, a type of scanning microscope that softly touches molecules instead of looking at them directly. The microscope is able to zoom in a thousand times smaller than is possible with a conventional light microscope. The researchers have demonstrated their method by folding RNA structures that form honeycomb shapes, but many other shapes should be realizable.

"We designed the RNA molecules to fold into honeycomb patterns because they are easy to recognize in the microscope. In one experiment we caught the polymerases in the process of making the RNAs that assemble into honeycombs, and they really look like honey bees in action," Geary continues.

Better and cheaper

A method for making origami shapes out of DNA has been around for almost a decade, and has since created many applications for molecular scaffolds. However, RNA has some important advantages over its chemical cousin DNA that make it an attractive alternative:

Paul Rothemund, a research professor at the California Institute of Technology and the inventor of the DNA origami method, is also an author on the new RNA origami work.

“The parts for a DNA origami cannot easily be written into the genome of an organism. RNA origami, on the other hand, can be represented as a DNA gene, which in cells is transcribed into RNA by a protein machine called RNA polymerase," explains Rothemund.

Rothemund further adds, "The payoff is that unlike DNA origami, which are expensive and have to be made outside of cells, RNA origami should be able to be grown cheaply in large quantities, simply by growing bacteria with genes for them. Genes and bacteria cost essentially nothing to share, and so RNA origami will be easily exchanged between scientists.”

Self-assembling scaffolds

The research was performed at laboratories at Aarhus University in Denmark, and the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. Ebbe Andersen, an Assistant Professor at Aarhus University, who works on developing molecular biosensors, lead the development of the project.

"All of the molecules and structures that form inside of living cells are the products of self-assembly, but we still know very little about how self-assembly actually works. By designing and testing self-assembling RNA shapes, we have begun to shed some light on fundamental principles of self-assembly." says Andersen.

"The primary application for these molecular shapes is to build scaffolds for arranging other microscopic components, such as proteins, into groups that allow them to work together. For example, using the scaffolds as a foundation to build a microscopic chemical factory in which products are passed from one protein enzyme to the next," Andersen explains.

See the animation showing an artist's impression of an RNA origami structure folding while it is being enzymatically synthesized.

Read the scientific article in Science: A single-stranded architecture for cotranscriptional folding of RNA nanostructures. Science, 2014; 345 (6198): 799 DOI: 10.1126/science.1253920

Facts:

How do RNAs fold?

RNA molecules are strands that are composed of A, U, C and G nucleotides. A single strand of RNA can fold back on itself by forming base pairs, interactions between individual nucleotides in the strand. The strongest base pairs in RNA are G-C, A-U and G-U, but many other base pairs can form in RNA as well. By contrast, DNA only pairs G-C and A-T, with far fewer exceptions. As a result, RNA has a greater funtional capacity compared to DNA, but is also more difficult to engineer due to the greater complexity. In biology RNA serves a wide variety of very different roles, but is mostly known for its central role in the production of proteins. To perform these functions RNA folds up on itself and forms complicated functional shapes. By studying the architecture of the RNA molecules from nature, scientist have identified 3D modules that are defined by a patterns of A, U, C and Gs. Scientists working with RNA have shown that these modules can be used like Lego bricks.

How to design RNA origami?

The design of RNA origamis is done with assistance from computer algorithms. The designer combines RNA helices and other 3D modules to form one interconnected strand using a 3D modeling environment. In this way the strand already has a set of sequence patterns defined, because the 3D modules constrain the sequence. Next, the strand is fed to a computer program that suggests the remaining A, U, C and Gs to assign to the rest of the structure, such that each part of the structure has a unique pattern that matches up. The program chooses the sequence from a very large space of solutions by testing many random sequences and then evaluating and comparing the energies of the base pairs from each input. After a target sequence is designed for a desired RNA, it can then be encoded into a DNA strand by a company specializing in DNA synthesis. As the price of gene synthesis continues to decrease, this allows larger and more sophisticated RNA designs to be tested. DNA genes for encoding RNA structures can be cost effective, since once the DNA for a design is synthesized it can be copied many times in the lab and even shared among researchers. When polymerase enzymes are added to the DNA genes, each copy of a DNA can be used to produce thousands of the encoded RNA structures.

For further information

Ebbe Sloth Andersen

Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics/iNANO, Aarhus University, Denmark

phone +45 41178619. Email: esa@inano.au.dk.